The narrative emerging from COP30 has been predictably familiar – disappointment over the absence of fossil fuel language in the final text, concerns about inadequate ambition, and questions about whether multilateral climate processes can still deliver. But for those of us on the ground in Belém, a different story emerged – one of tangible progress, shifting priorities, and the transformative presence of indigenous voices.

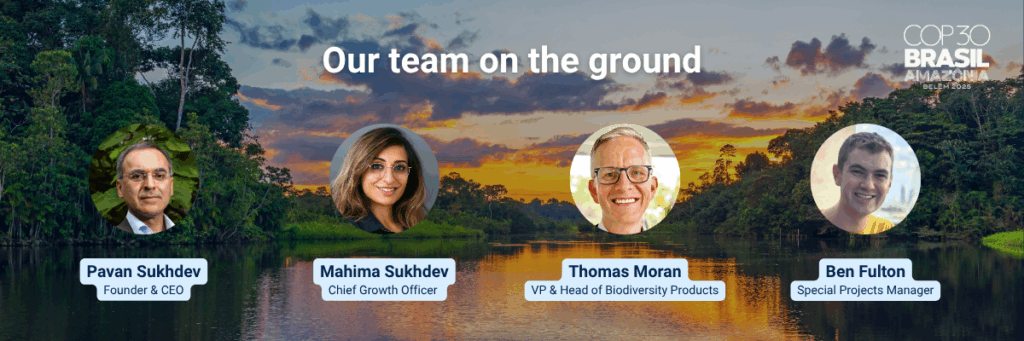

GIST Impact attended both pre-COP30 in São Paulo and COP30 in Belém, and the team’s perspectives reveal a more nuanced picture of what this “implementation COP” actually achieved.

Representation is key

Mahima Sukhdev, GIST Impact’s Chief Growth Officer, was struck by how the forest setting fundamentally shifted the conversation. Being set in a location deep within the Amazon rainforest meant that nature-based solutions and the role of ecosystems in addressing climate challenges were woven throughout discussions in a way they simply couldn’t be ignored and hadn’t been at previous COPs.

But the most significant change was in indigenous representation. Their presence wasn’t tokenistic or limited to a handful of ceremonial appearances. Instead, hundreds of people from indigenous communities moved through the Blue and Green Zones, participating in panels, asking questions in plenary sessions, and holding substantive meetings with policymakers and private sector representatives.

This visibility translated into concrete outcomes. The conference saw historic commitments for Indigenous Peoples and local communities, including a global pledge to recognise 160 million hectares of indigenous lands and a renewed $1.8 billion Forest and Land Tenure Pledge. This wasn’t just symbolic – it represented a fundamental shift in who shapes climate conversations and whose knowledge is centred in solutions.

The timing of this proved particularly significant for GIST Impact’s work. When Mahima met with an indigenous chief (pictured above) who asked whether investors even care about Indigenous communities, she could point to Storebrand’s recent report, where GIST Impact provided the data, and tangibly show how investors are focusing on indigenous lands. This work was subsequently featured in TNFD’s nature transition planning guidance published during the COP (see pg. 43-45).

Shifting focus

Thomas Moran (VP and Head of Nature & Biodiversity Products) and Ben Fulton (Manager of Special Projects) identified an important change in how climate action is being framed. The dominant theme throughout the conference was a shift from talking about benefits for nature to focusing squarely on how climate action benefits people. This wasn’t just rhetorical – it represented a reframing designed to cut across political divides by emphasising affordability, welfare, and overall quality of life.

Ben noticed another pivot from focusing on ‘staying below 1.5 degrees’ to ‘adaptation for a hotter world’. Rather than viewing this as defeatism, both recognised it as pragmatic realism that enables more productive and science-aligned conversations. For businesses, this translates to clearer value propositions and a welcomed consensus on one of the key overarching sustainability metrics.

What COPs actually do (and what they don’t)

Whilst headlines focused on the absence of fossil fuel language in the final text, this criticism fundamentally misunderstands what COPs are designed to achieve. The same parties who have held entrenched positions since the COP process began were never going to change those positions overnight during a two-week conference.

Instead, COPs – whether focusing on climate, biodiversity or desertification – function as consensus-building platforms that set agendas, form working groups, and create launchpads for action between conferences. This proved itself – COP30, more than 80 countries backed plans for developing a roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels, with Colombia and the Netherlands announcing they would co-host a fossil fuel phase-out meeting in April 2026.

Much of the commentary around COP30 has focused on what wasn’t achieved, and this misses the forest for the trees. Understanding what COPs can and cannot achieve is essential for evaluating their success. They’re not designed to solve climate change in two weeks. They’re designed to build consensus, launch initiatives, and create the frameworks and partnerships that enable action over the months and years that follow.

By that measure, COP30 succeeded. The real test will be what happens next – in boardrooms, in national capitals, and in the forests and indigenous territories that were so visible in Belém.